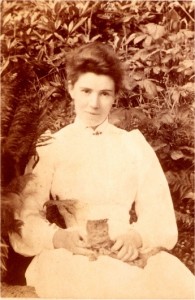

Amy Wilson Carmichael

1867-1951

Amy Wilson Carmichael (16 December 1867 – 18 January 1951) was a Protestant Christian missionary in India, who opened an orphanage and founded a mission in Dohnavur. She served in India for fifty-five years without furlough and authored many books about the missionary work there.

Amy Wilson Carmichael (16 December 1867 – 18 January 1951) was a Protestant Christian missionary in India, who opened an orphanage and founded a mission in Dohnavur. She served in India for fifty-five years without furlough and authored many books about the missionary work there.

Early life

Amy Wilson Carmichael was born in the small village of Millisle, County Down, Northern Ireland to David and Catherine Carmichael. Her parents were devout Presbyterians and she was the eldest of seven siblings. One story of Carmichael’s early life tells that as a child, she wished that she had blue eyes rather than brown. She often prayed that Jesus would change her eye color and was disappointed when it never happened. She loved to pinch her brother’s cheeks to make the prettiest color blue in his eyes. But she always repented afterwards for hurting her brother. As an adult, however, she realized that, because people from India have brown eyes, she would have had a much more difficult time gaining their acceptance if her eyes had been blue.

Carmichael’s father died when she was 18. Carmichael was the founder of the Welcome Evangelical Church in Belfast. The Welcome’s story begins with Carmichael in the mid 1880’s starting a Sunday morning class for the ‘Shawlies’, i.e. the mill girls who wore shawls instead of hats, in the church hall of Rosemary Street Presbyterian which proved to be very successful. Amy’s work among the shawlies grew and grew until they needed a hall to seat 500 people. At this time Amy saw an advertisement in The Christian by which an iron hall could be erected for £500 that would seat 500 people.

A donation of £500 from Miss Kate Mitchell, and a donation of a plot of land from one of the mill owners saw the erection of the first Welcome hall on the corner of Cambrai Street and Heather Street in 1887. Amy continued at the Welcome until she received a call to work among the mill girls of Manchester in 1889 before moving onto missionary work. In many ways she was an unlikely candidate for missionary work. She suffered neuralgia, a disease of the nerves that made her whole body weak and achy and often put her in bed for weeks on end. It was at the Keswick Convention of 1887 that she heard Hudson Taylor, founder of the China Inland Mission speak about missionary life. Soon afterward, she became convinced of her calling to missionary work. She applied to the China Inland Mission and lived in London at the training house for women, where she met author and missionary to China, Mary Geraldine Guinness, who encouraged her to pursue missionary work. She was ready to sail for Asia at one point, when it was determined that her health made her unfit for the work. She postponed her missionary career with the CIM and decided later to join the Church Missionary Society…..

Amy Carmichael with Indian children

Initially Carmichael traveled to Japan for fifteen months, but after a brief period of service in Sri Lanka, she found her lifelong vocation in India. She was commissioned by the Church of England Zenana Mission. Hindu temple children were young girls dedicated to the gods and forced into prostitution to earn money for the priests. Much of her work was with young ladies, some of whom were saved from forced prostitution. The organization she founded was known as the Dohnavur Fellowship. Dohnavur is situated in Tamil Nadu, thirty miles from the southern tip of India. The fellowship would become a sanctuary for over one thousand children who would otherwise have faced a bleak future.

In an effort to respect Indian culture, members of the organization wore Indian dress and the children were given Indian names. She herself dressed in Indian clothes, dyed her skin with dark coffee, and often traveled long distances on India’s hot, dusty roads to save just one child from suffering.

While serving in India, Amy received a letter from a young lady who was considering life as a missionary. She asked Amy, “What is missionary life like?” Amy wrote back saying simply,

“ “Missionary life is simply a chance to die.” ”

Carmichael’s work also extended to the printed page. She was a prolific writer, producing thirty-five published books including Things as They Are: Mission Work in Southern India (1903), His Thoughts Said . . . His Father Said (1951), If (1953), Edges of His Ways (1955) and God’s Missionary (1957).

Final days and legacy

In 1931, Carmichael was badly injured in a fall, which left her bedridden much of the time until her death. She died in India in 1951 at the age of 83. She asked that no stone be put over her grave; instead, the children she had cared for put a bird bath over it with the single inscription “Amma”, which means mother in the Tamil.

Her biography quotes her as saying:

“ “One can give without loving, but one cannot love without giving.” ”

Her example as a missionary inspired others (including Jim Elliot and his wife Elisabeth Elliot) to pursue a similar vocation.