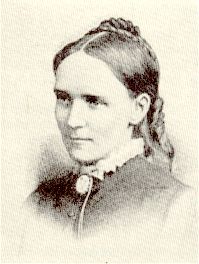

Mary Slessor

(2 December 1848 – 13 January 1915)

“Run, Ma! Run!” Whenever Ma, the white woman, heard these words she knew that serious trouble was brewing, so she hurried out of the house and down the path into the forest. Presently she found Etim, the oldest son and heir apparent of chief Edem, lying unconscious under a tree which had fallen on him. For a fortnight she nursed him in his mother’s house, but her efforts were in vain.

“Run, Ma! Run!” Whenever Ma, the white woman, heard these words she knew that serious trouble was brewing, so she hurried out of the house and down the path into the forest. Presently she found Etim, the oldest son and heir apparent of chief Edem, lying unconscious under a tree which had fallen on him. For a fortnight she nursed him in his mother’s house, but her efforts were in vain.

Early one Sunday morning, while she was resting in her own hut, the boy’s life began to ebb. This news sent a spasm of terror throughout the district, for every violent death was attributed to witchcraft and it was certain that a number of persons would be put to death on the charge of having caused the tree to fall on the boy. Hurrying to the chief’s house, Ma found the natives blowing smoke into the dying lad’s nostrils, shouting into his ears and rubbing ground pepper into his eyes. As soon as life had fled, the chief shouted: “Sorcerers have killed my son and they must die! Bring the witch-doctor!”

At these words everybody fled. When the witch doctor arrived, he tried out his divinations and placed the responsibility for the boy’s death on a certain village. Forthwith armed warriors marched to that village, seized a dozen men and women, brought them back loaded with chains and fastened them to posts in the yard…

The chief endeavored to persuade Ma to let the prisoners submit to the poison ordeal, for, said he, “If they are not guilty, they will not die.” Ma knew that the poison would kill them, irrespective of their innocence, and refused to agree.

Finally, eleven of the prisoners were released and the death of the one remaining, a woman, was demanded. When Ma stubbornly refused, the chief stormed, threatened to burn down the house, and in blazing passion declared, “She caused my son’s death and she must die!” Bowing her head, the white Ma prayed for strength and patience and love. And, after several days of terrific strain she eventually won out. The last of the prisoners was released and the chief contented himself with the sacrifice of a cow. It was the first time in this entire district that a chief’s grave had not been saturated with human blood.

How was the lone white woman able to endure this long and terrible ordeal? Let her give the answer: “Had I not felt my Saviour close beside me, I would have lost my reason.” Empowered by that divine Presence, she held her ground and preached to the natives. Quoting the words of Jesus, “He that heareth my word, and believeth on him that sent me, hath everlasting life, and shall not come into condemnation; but is passed from death unto life,” she sought to show the terrors of divine judgment and the wonders of life everlasting.

Who was this woman who could triumph over such conditions? She was Mary Slessor, born in Aberdeen, Scotland, December 2, 1848, and known as the White Queen of Calabar, a region on the west coast of Africa. Concerning this intrepid woman, J. H. Morrison pays this tribute: “She is entitled to a place in the front ranks of the heroines of history, and if goodness be counted an essential element of true greatness, if eminence be reckoned by love and self-sacrifice, by years of endurance and suffering, by a life of sustained heroism and purest devotion, it will be found difficult, if not impossible, to name her equal.”

She was indeed a queen — a queen ruling in love over natives in Africa and a queen among the heroines of the Christian church.

I. The Queen and Her Royal Retinue

One day in 1898 the newsboys and porters in Waverley Station, Edinburgh, were astonished to see a woman of slight build, with a face like yellow parchment in hue and with short straight hair, get off the train accompanied by four wide-eyed African girls. The spectators’ amazement would have been vastly intensified had they known that they were gazing at a queen and her retinue; that, in early life she was the mainstay of the family after her father’s death at Dundee and had been a Scottish factory girl, toiling at her weaving machine from six in the morning till six at night amid the flash of the shuttles, the rattle of the looms and the roar of the machines; and, like David Livingstone, had educated herself by reading good books, a few sentences at a time, while tending her machine.

Wherever Mary Slessor went on her triumphal tour among the churches, the people were enthralled as they heard her tell, in a simple and humble manner, how she had endured hunger and thirst under the flaming sun of Africa, had been smitten down by tropical fevers, had controlled drunken cannibals brandishing loaded muskets, had mastered hundreds of frenzied natives lusting for blood and had faced death a thousand times in her endeavor to bring redemption’s story to Africa’s perishing peoples. They were moved to tears as she told of the slave markets, of human sacrifice, of cannibalism, and told specifically how, upon a certain chief’s death, twenty-five heads were cut off and, at the death of another chief, sixty people were killed and eaten. But the stories the Scotch Christians liked best of all were those telling how she had rescued from death hundreds of baby twins and other deserted babies thrown out in the forest to perish of hunger or to be eaten by ants or leopards. The stories were made doubly impressive by the presence of four of these children who had been cast off and then rescued.

II. The Queen and Her Royal Mission

As a young girl, Mary had given her heart and life to Jesus and, due to the influence of stories told her by her mother, had formed a secret desire to be a missionary to Calabar. She became not only an active member of her own church but also a zealous worker in several missions. Early in 1874 the news of the death of David Livingstone stirred the land and created a great wave of missionary enthusiasm. The call for workers for Africa thrilled many a heart into action. One of these was Mary Slessor. She offered her services to the Foreign Mission Board, was accepted and brought to Edinburgh for special training. August 5, 1876, she sailed from Liverpool on the steamer Ethiopia. Seeing a large number of casks of spirits being loaded, she exclaimed ruefully: “Scores of casks of rum and only one missionary!”

Soon after landing in Calabar she began to realize the difficulty and seeming impossibility of the work to which she had committed herself. She saw huge, hideous alligators sunning on the mud banks and swimming in the streams. One day her canoe was attacked by a hippopotamus and she saved her life, and the lives of the children with her, by throwing a cooking pot into the gaping jaws. She saw the barracoons where the captured natives were penned until the slave-ships arrived. She found herself in a land where terrified prisoners dipped their hands in boiling oil to test their guilt under some accusation, where wives were strangled or buried alive to go with their dead chief into the spirit-world, where heartless chiefs could order a score of men and women to be beheaded for a cannibal orgy and sell a hundred more into the horrors of slavery. What could one frail, timid woman do, confronted by such an appalling situation? Overwhelmed and depressed, she knelt and prayed, “Lord, the task is impossible for me but not for Thee. Lead the way and I will follow.” Rising, she said, “Why should I fear? I am on a Royal Mission. I am in the service of the King of kings.”

She commenced the study of Efik, the language of the Calabar people, and in time mastered it so that the natives admitted that she could use their tongue better than they themselves could.

What a memorable day it was when she went out on her first “preaching” trip. Two boys carried a drum and beat it to call the people together. Hearing that a white woman was in the vicinity, a great crowd quickly gathered. Her first message to the dark throng of superstitious and barbaric Africans was delivered under the shade of a large tree beside a devil-house built for a dead man’s spirit. After reading John 5:1-24, she spoke in tender tones, dwelling especially on verse 24: “Verily, verily, I say unto you, He that heareth my word, and believeth on him that sent me, hath everlasting life, and shall not come into condemnation; but is passed from death unto life.”

In a land of death, she brought a message of life. To souls in deepest sorrow, she brought a message of comfort and hope. To people dwelling in the habitations of cruelty, she spoke of love and kindness. To lives steeped in barbarism and sin, she pointed to the redeeming Lord.

“In Christ,” the missionary says, “we become new creatures. His life becomes ours. Take that word life and turn it over and over and press it and try to measure it, and see what it will yield. Eternal life is a magnificent idea which comprises everything the heart can yearn after. Do not your hearts yearn for this life, this blessed and eternal life, which the Son of God so freely offers?”

“From death in this world unto life in the next,” says Jesus.

“If we be dead with Christ, we shall also live with Him,” says Paul.

“Eternal life comprises everything the heart can yearn after,” says Mary Slessor.

III. The Queen and Her Subjects

Mary wanted to leave the coast and live in the interior, in the midst of the head-hunters and cannibals. When one of the men missionaries went into this district to seek permission to settle, he was captured and narrowly escaped with his life. Nevertheless, Mary determined to go. “I must go forward and onward,” she declared. On the third of August, 1888, she set out on her great adventure. She stepped into the canoe with five native orphans, children she had rescued from death, the oldest a boy of eleven, the youngest a baby in her arms. All day long it rained. Night had fallen when the canoe was pulled up in the river bank. The village of Ekenge, to which they were going, lay four miles back in the forest. Taking the baby in her arms and urging forward the weeping children who were terrified by the darkness and the knowledge that snakes and leopards abounded, Mary struck out along the forest path, leaving the men to follow with the bundles of food and clothing. Soaking wet, hungry and exhausted they waited for the loads to arrive. After awhile news reached her that the men were tired and had gone to sleep in the boat. Exhausted as she was, Mary retraced the four miles through the forest, aroused the sleeping men in the canoe and brought them all on to Ekenge by midnight. It was this indomitable spirit which in subsequent years carried her through a thousand toils and perils where most women would have given up in despair.

The chief liked her brave spirit and gave her permission to stay in the village. She soon made herself quite at home among the people. With her own hands she helped in the building of a mud-walled house. Incredible as it sounds, she went about with bare head and bare feet, lived on native food, drank unfiltered water, slept on the ground, and did many other things that would have quickly brought death to any ordinary person. Two incidents out of a thousand will illustrate how she defied perils and won over the natives with nought but love and courage.

A Journey of Perils

A strange quiet lay over the village by the river and the Calabar people were in great suspense, for the chief was ill and they knew that if he died many of them would be slain to be his attendants in the spirit world. Presently a woman who was a visitor from another village entered the chief’s harem and said to his wives, “Through the forest at Ekenge there lives a white Ma who by her magic can cast out the demons who are killing your chief. She saved my own child and has done many other wonders by the power of her juju. Why don’t you send for her?” The women were eager to do this, for their very lives depended on the chief getting well. When they told the chief about the strange white woman, he ordered: “Send for her at once.”

All through the day the messengers hurried across streams and through the forest till at last, after a journey of eight hours, they came to Ekenge. Coming to Mary’s house they told their mission. She knew that the way was full of perils but she also knew that if the chief died, scores of lives would be sacrificed. “I must go,” she said. Chief Edem tried to restrain her: “There are warriors out in the woods and you will be killed. You must not go.” Ma Eme, a fat African widow who loved Mary, declared, “The rains have come. The streams are deep. The woods are full of wild beasts. You could never get there.” But the missionary lady said, “I must go.”

All through the night she lay awake, wondering if she should go on such a journey with so many risks and only a possibility of saving the sick chief’s life. Early in the morning she knelt, praying that she might know the will of God in the matter. Assured in her heart that her Lord would accompany her, she set out at dawn. All day unceasing torrents of rain fell. Soon it became impossible to walk in her water-soaked boots, so she threw them into the bush and plowed on through the mud with bare feet. On and on she went, her head throbbing with fever, her weak and trembling body being driven forward by a dauntless spirit till, after more than eight hours of walking, she staggered into the house of the sick chief.

Although wet, exhausted, hungry and aching all over from fever, Ma did not lie down for even a moment’s rest but went immediately to the chief who lay unconscious on a mat on the mud floor. After examining him she took from her little medicine chest a certain drug and gave him a dose. She continued to nurse him and the next day, to the astonishment of all the villagers, the chief regained consciousness and took food. Some days later he was quite well and all the people laughed and sang for joy, knowing that there would be no slaying.

In gratitude and wonder they gathered around Mary Slessor and inquired concerning her magic powers. She said to them: “I have come to you because I love and worship Jesus Christ, the Great Physician and Saviour, the Son of the Father God who made all things. I want you to know this Father and to receive the eternal life which Jesus offers to all those with contrite and believing hearts. To know Jesus means to love Him, and with His love in our hearts we love everybody. Eternal life means peace and joy in this world and a wonderful home in the next world. My heart longs for you to believe in Jesus, to walk in His paths, and to know the blessings of eternal life through Him.”

Years passed by and the white Ma’s name was known far and wide. They knew her to be good and brave and kind, but they thought she was mad because she was always rescuing twin babies upon whom rested a curse, according to the Calabar people. She was held in such high esteem, the chiefs often asked her to help them decide quarrels and in palavers between villages she often kept the people from going to war. They thought her notions very strange, but many of them began to realize that her brave and loving spirit came from the great God of whom she spoke so much.

Dangers Defied

One day she received a secret message saying that, in a district far away, a man of one village had wounded the chief of another village and that the warriors of both villages were holding a council of war. “I must go and stop it, else much blood will be spilt and many will be killed,” said Mary Slessor. “No, you cannot,” replied her friends at Ekenge. “You have been ill and can scarcely walk. There are wild beasts lurking in the woods. The warriors are out and will kill you in the dark, not knowing who you are.” “I must go,” she said and quickly made ready. Accompanied by two men with lanterns she set out through the darkness. At midnight she came to a certain village and asked the chief to provide her with a drummer so that people might know, on hearing the drum, that a protected person was travelling.

The chief was surly. “You are going to a warlike people,” he said. “You are likely to get killed on the way. Anyhow, they would not listen to what a woman says.” Mary took this as a challenge. “When you think of the woman’s power,” she said to the chief, “you forget the power of the woman’s God. I shall go on.” Whereupon she plunged into the darkness. The villagers thought she must be mad, to defy their chief, who had the power to kill her, and to go into the forest where at any moment she might be killed by ferocious leopards or by savages infuriated by anger and by drink.

At dawn she came to the place where a large company of warriors were preparing to assault a village. She was too weary to walk, but her attendants shouted, “Run, Ma, Run!” She heard wild yells and the roll of war drums. Running as fast as she could, she caught up with the maddened warriors and demanded that they desist from fighting. Stunned by her courage, they hesitated, while she walked boldly toward a regiment of fierce savages standing in the village ready to fight. Drawing near she called out, “I have come to help you settle this matter peaceably and justly. There is no need to shed many lives.” Just then, to her amazement, an old chief stepped toward her and knelt down at her feet! “Ma,” he said, “we are glad you came. We admit that one of our drunken young men wounded the chief over there. It was an act in which the rest of us had no part. We are glad for you to speak with our enemy and help make peace.”

Looking into the man’s face, she saw to her joy that this was the very chief who was about to die several years before and whom she had cured by going on that long, dangerous journey through the forest in the rain. How glad she was that she had gone and that now she could be a peacemaker between the two parties of wild savages, who, if she had not come, would have fought to the death.

IV. The Queen’s Final Coronation

Though stricken with fever, diarrhea, and other diseases scores of times, she toiled on in Calabar for nearly forty years.

Repeatedly she moved deeper into the interior to take redemption’s sweet story to new tribes and new areas. “Anywhere, provided it be forward” was an oft-repeated saying of hers. Her house was filled with orphans, upon whom she lavished the love of her motherly heart. She had a string running from her cot to the hammock of each of the twenty-five or thirty little ones, so that, whenever one of them began to fret or cry in the night — as often happened — she could pull the right string and swing the youngster to sleep.

She supervised the building of a new house every time she moved. The earlier houses were very simple structures. Eventually she built a house with a cement floor. When an incredulous visitor inquired how she managed to mix the cement, she replied, “All I did was to stir it like porridge and pray!”

During an epidemic of smallpox the people fled in terror of the dread disease. Ma nursed and fed the forsaken victims, tenderly pointed them to Jesus, and, without assistance, buried the many who died. In a letter describing her experiences she wrote: “It is not easy. But Christ is here and I am always satisfied and happy in His love.”

Miss Slessor worked from cock-crow till star-shine. And what was the grand object of all her striving and ordeals? One who knew her well stated, “It was for souls she was always hungering.” One night she walked twelve miles through the bush to reach a dying woman and rescue her twins from death. As life ebbed away, the poor woman who had experienced so much of cruelty as a slave and the disgrace of giving birth to twins, listened wistfully as Mary told of a Saviour’s love and of a heaven of happiness to be forever her portion, if in sincerity she would heed the gracious invitation of Mary’s favorite text: “He that heareth my words and believeth … is passed from death unto life.”

Mary rescued hundreds of twin babies thrown out into the forest, prevented many wars, stopped the practice of trying to determine guilt by the poison ordeal, healed the sick, and unweariedly told the people about the great God of love whose Son came to earth to die on the cross that poor sinful human beings might have eternal life. The Master she loved and served so ardently crowned her labors by permitting her to establish a number of churches and to see hundreds of erstwhile savages partake of the sacred emblems of their Saviour’s death.

Shortly before her death, January 13, 1915, she said to her twins, now grown to young manhood and womanhood: “Never talk about the cold hand of death. It is the hand of Christ. For I am persuaded, with the apostle Paul, that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” Another time she said, “The time of the singing of birds is where Christ is.” For Mary Slessor, the winter was past, the tempests were over and the time of the singing of the birds had come. At the last she was thinking of the love of Christ and the glories of life eternal.

Mary Slessor, the Queen of Calabar, was constrained to offer to her Lord her very best, and with gladness she broke the alabaster box of her consecrated life and gave the precious ointment to Him for the redemption of many in Africa. “Life is so grand and eternity is so real,” she had said. When she crossed over the river, she carried an armful of precious sheaves, gathered amidst much toil and tribulation, and she received from the hand of her adored Lord the soul-winner’s “crown of rejoicing.”

by Eugene Myers Harrison

![hamilton[1]](http://www.wellsofgrace.com/test/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/hamilton1.jpg)

![aylward[1]](http://www.wellsofgrace.com/test/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/aylward11.jpg)

![Yu-Ci-Du[3]](http://www.wellsofgrace.com/test/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Yu-Ci-Du3-e1339090833284.jpg)

![chapman_helen[1]](http://www.wellsofgrace.com/test/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/chapman_helen1.jpg)